Examining Differences in the Substance and Enforcement of Patent Laws in the US and China

Share

This article is the first of a two-part series by Eugene Liu. The second installment will be published next week.

On March 22nd, 2018, President Donald Trump announced that his administration would impose tariffs on up to $50 billion dollars worth of Chinese imports. According to the Trump administration, the tariffs were in response to China’s unfair economic practices. In his speech that very day, President Trump accused China of stealing intellectual property, restricting foreign ownership and investment to force technology transfers, devaluing its currency to gain an unfair export advantage, and employing cyber attacks to disrupt US institutions.

Midnight of June 8th 2018, the Trump administration officially imposed 25% tariffs on $34 billion dollars worth of Chinese imports including steel, water heaters, and airplane tires. China responded by imposing 25% tariffs to $34 billion dollars worth of American imports including pork, soybeans, and motorcycles. The Trump administration has cited many reasons for the tariffs, but the primary concern may be China’s inadequate protection of intellectual property.

Intellectual property violations have long been a point of contention in US-China economic relations. In 1989, the US listed China in its first Special 301 Report as a country with questionable intellectual property protection and enforcement. For the sake of length, this article will focus on patents—specifically differences in legal text and enforcement measures between the US and China.

US and China use different criteria when determining the amount of damages to be awarded for patent infringement. China takes into account the benefit received by the infringer while the US does not. The two countries also differ in the standards applied to each criteria. For example, while the US and China both consider the patentee’s actual losses when determining damages, the scope of what can be considered an “actual loss” varies. Moreover, the US allows for punitive damages, while China does not. This critical difference greatly impacts the final sum of damages awarded.

With regards to enforcement, damages in China are most often determined by a court’s discretion. In these cases, there is no way to access the process by which damages are determined because the court’s deliberation is privileged. This is not the case in the US, where reasonable royalties are the most common method for determining damages. Because China establishes a maximum limit on the sum of damages a court can award by its discretion, damages awards are much lower in China than in the US. This is indicative of weaker intellectual property protection because offenders are not fined as much and therefore are less likely to be deterred from future infringements.

Another difference in the enforcement of patent laws in the US and China arises in the division of labor between administrative and judicial channels. In China, the majority of patent disputes are settled through administrative entities such as the State Intellectual Property Office. This is because administrative entities in China are often faster and cheaper than the courts. In the US, however, administrative entities such as the United States Patent and Trademark Office and the International Trade Commission do not have authority to settle domestic patent disputes. As such, almost all patent disputes are settled by the courts. The case can be made that a judicature-heavy patent dispute resolution system is insulated from the corruption and mismanagement easily cultured in administrative entities.

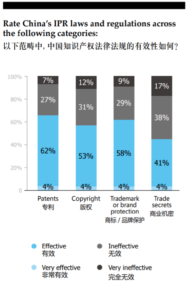

American Ratings of Intellectual Property Laws and Regulations in China

American businesses see China’s patent laws and regulations as being the most effective among all sectors of intellectual property laws and regulations. According to an annual report released by the American Chamber of Commerce in the PRC, 62% of American respondents reported they believed China’s patent laws and regulations were effective, that number was 58%, 53% and 41% for trademarks, copyrights, and trade secrets respectively, with trade secrets receiving the lowest effectiveness percentage. Although more than 50% of American businesses reported they were satisfied with China’s patent laws and regulations, the general consensus is that China still has much room for improvement.

American businesses see China’s patent laws and regulations as being the most effective among all sectors of intellectual property laws and regulations. According to an annual report released by the American Chamber of Commerce in the PRC, 62% of American respondents reported they believed China’s patent laws and regulations were effective, that number was 58%, 53% and 41% for trademarks, copyrights, and trade secrets respectively, with trade secrets receiving the lowest effectiveness percentage. Although more than 50% of American businesses reported they were satisfied with China’s patent laws and regulations, the general consensus is that China still has much room for improvement.

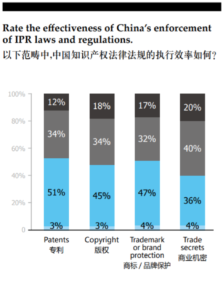

American Ratings of the Enforcement of Intellectual Property Laws and Regulations in China

When asked to rate the effectiveness of enforcement of intellectual property laws, however, effectiveness ratings dropped across the board. For all sectors of intellectual property, an average of 45% of respondents believed that the enforcement laws and regulations was effective. To put it simply, American businesses are less satisfied with the enforcement of laws and regulations than they are with laws and regulations themselves. Thus the American consensus is that the Chinese government should prioritize the enforcement of existing laws and regulations before creating new ones.

When asked to rate the effectiveness of enforcement of intellectual property laws, however, effectiveness ratings dropped across the board. For all sectors of intellectual property, an average of 45% of respondents believed that the enforcement laws and regulations was effective. To put it simply, American businesses are less satisfied with the enforcement of laws and regulations than they are with laws and regulations themselves. Thus the American consensus is that the Chinese government should prioritize the enforcement of existing laws and regulations before creating new ones.

US and China Patent Laws: Different Criteria for Evaluating Damages and Different Standards within Each Individual Criteria

Article 65 of China’s Patent Law establishes four successive criteria for determining the amount of damages to be awarded in patent infringement cases:

(1) The patentee’s actual losses, most likely a loss of profit;

(2) The benefit received by the infringer, because the benefits of the infringer are assumed to be the losses of the patentee;

(3) The royalties lost from the infringement, taking into account the appropriate multiplier derived from the scope and magnitude of infringement;

(4) The decision of the People’s Court. The Court can determine any amount of damages to be paid up to $1 million RMB (approximately $156,100 USD).

While Section 284 of Title 35 of the US Code establishes three successive criteria for determining the amount of damages to be awarded:

(1) The patentee’s actual losses, interest, and other costs, under the condition that they are not less than the royalties owed to the patentee by the infringer;

(2) Reasonable royalties;

(2) The Court’s decision (the court may increase the damages up to three times the amount found or assessed)

The Patentee’s Actual Losses

Although the US and China both take into account the patentee’s actual losses when determining the amount of damages to be awarded, the scope of what is considered the patentee’s actual losses is much narrower in China. Article 20 of the “Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Law to Trial of Cases of Patent Disputes” adopted by China in 2001 establishes four standards for determining the actual losses of the patentee:

(1) The total of the infringing products sold in the market times the reasonable profit of each infringing product;

(2) The total reduction in the volume of sale by the rightsholder;

(3) The income of the infringer from the infringement (generally counted according to the business profit of the infringer or, for the infringer who solely engages in infringement as its or his entire business, the income may be computed according to its or his sales profit);

The Chinese criteria for determining the patentee’s actual losses takes a sales-heavy approach, while the US employs a broader evaluation—taking not only sales into account, but also the operating costs of the patentee, and damages to the patentee’s reputation among other factors.

Reasonable Royalties

The US and China both consider reasonable royalties when determining damages awards in cases of patent infringement. Once again, however, the benchmarks for determining reasonable royalties vary. Article 21 of the “Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Law to Trial of Cases of Patent Disputes” adopted by China in 2001 establishes five successive standards for determining the sum of reasonable royalties.

(1) The kind of patent right involved

(2) The nature and facts of the infringement by the infringer

(3) The amount of the patent licensing fee

(4) The nature, extent and time of the patent license with reference to one to three times the patent licensing fee;

(5) The Court’s decision. Where there is no patent licensing fee to be referred to or the license fee is obviously unreasonable, the people’s court may, according to the factors, such as the kind of the patent right, the nature and facts of the infringement, determine the amount of compensation of more than RMB 5,000 Yuan and less than RMB 300,000 Yuan, but not exceeding RMB 500,000 Yuan at most.

In determining reasonable royalties, China only employs the above standards if there exists a clear record of the patentee licensing the patent under question to a third party. In the US, judges use hypothetical negotiation and the analytical method to determine the amount of reasonable royalties, regardless of whether or not the patent under question was licensed to a third party. The hypothetical negotiation approach assumes that a negotiation took place between the willing-licensor and the willing-licensee, and uses the factors in the hypothetical negotiation to compute a sum. The analytical method uses the patentee’s internal profit projections to arrive at a sum.

Benefit Received by the Infringer

In 1947, the US removed the criteria of benefits received by the infringer when determining damages awards in patent infringement cases. In China, however, this criteria still exists. Article 16 of the “Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Law to Trial of Cases of Patent Disputes” adopted by China in 2009 states:

The courts, in determining pursuant to Article 65.1 of the Patent Law the gains acquired by the infringer from the infringement, shall restrict the gains to those acquired by the infringer from the infringement upon the patent right itself, and those gains generated from other rights shall be reasonably deducted.

Compensatory vs. Punitive Damages

The last sentence of Section 284 of US Patent Law illustrates the distinction between China’s compensatory system of damages, and the US punitive system of damages. It reads: “In either event the court may increase the damages up to three times the amount found or assessed.” This allows for punitive damages in the US. The Court can, without additional justification, take any amount of compensatory damages and increase it up to three times. China’s Patent Law does not give the Court authority to multiply a determined amount, thus all damages are compensatory.

In an attempt to strengthen the protection of intellectual property, the Chinese Legislative Affairs Office in December 2015 included in Article 68 of their Fourth Amendment to the Chinese Patent Law a provision which would grant courts the authority to increase determined damages by up to three times, thus opening the door for the implementation of punitive damages. Chinese Premier Li Keqiang also announced during the Government Work Report at the 13th National People’s Congress in 2018 that China would implement punitive damages in cases of intellectual property infringement. This latest amendment to China’s patent law may soon be formally adopted.

Want to get involved?

Connect with us! Connect with us!