SFFA v. Harvard, SFFA v. UNC: The History Behind Affirmative Action and What Lies Ahead

Share

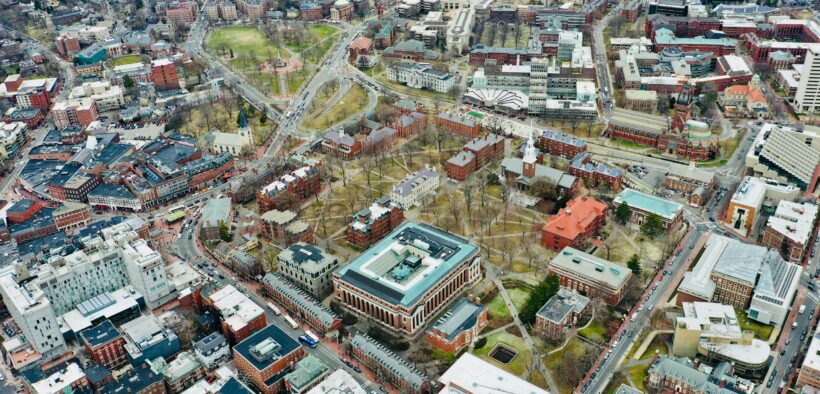

Image Credits: @henrydixon on Unsplash (Unsplash License)

June 29, 2023, was the end of an era for students across the nation. For marginalized students applying to college, especially to the most elite schools in the nation, affirmative action was protection that assured them that their racial and gender backgrounds would not affect their chances of getting into the school of their dreams. For these students, who had historically been shunned from elite institutions, affirmative action promised to take into consideration the barriers that they had to overcome, along with their merits and achievements in the admissions process. On June 29, all of that changed with the Supreme Court’s decision in Students for Fair Admissions, INC v. President and Fellows of Harvard College and Students for Fair Admissions, INC v. University of North Carolina (the two cases were consolidated due to the similarity of their content and though the considerations and decisions were done separately, ultimately, the Justices arrived at the same decision for both cases, which was given in a consolidated case). SFFA v. Harvard and SFFA v. UNC gutted the conventional affirmative action programs used by colleges and universities across the nation and narrowed what race-conscious admissions were considered constitutional as set forth by previous precedent.

The Origins of Affirmative Action

The modern concept of affirmative action first came into use in March of 1961 with President Kennedy’s Executive Order 10925. The order established that the government was obligated to protect the rights of US citizens through the promotion of equal opportunities in employment in public sectors with regard to race. The order created the President’s Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity, which would oversee that employment within government agencies would be in line with the federal policy of nondiscrimination on the basis of race. It also extended this policy to government contractors, requiring that they “take affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed, and that employees are treated during employment, without regard to their race, creed, color, or national origin.”

In 1964, these rights were expanded upon in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, which banned discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin in hiring, promoting, setting wages, training, or any other employment process. The act also created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) to oversee the implementation and maintenance of this law.

Under the Johnson administration, civil rights were again expanded with Executive Order 11246. The order expanded on the Civil Rights Act and Kennedy’s order to not just promote equal treatment, but to then require government contractors and subcontractors to make good-faith efforts in order to expand job opportunities for historically oppressed groups. The Nixon administration then furthered the goals of this policy through the Philadelphia Plan, which required that government contractors submit minority report goals as a part of their contracting bids. This move from Nixon helped to further civil rights through the promotion of disenfranchised groups, and it helped, along with the previously stated orders and laws, to create the landscape in which affirmative action in college admissions came to be. But, for education, the real affirmative action fight would not happen through legislation or through the President, but rather through the courts.

Affirmative Action, Education, and the Supreme Court

Perhaps one of the most important landmark cases in affirmative action, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, impacted and set the precedent for every case to follow. Allen Bakke, a white student, had been rejected from University of California Davis’ medical school twice and he claimed it was due to discrimination. The university set aside sixteen out of one hundred seats in a given class for qualified minority students, and with that, Bakke claimed that the university had violated the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The court ultimately decided that the quota system used by the university was unconstitutional as it did not adhere to the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. However, it did not deem all affirmative action programs unconstitutional. It deemed the use of race as one factor of many in the admissions process permissible under the constitution, as the state had a compelling interest in encouraging diversity under the 14th Amendment.

Since this case, the ideas around affirmative action have stayed relatively the same: race quotas in any capacity are not constitutional, but race-conscious admissions are, as long as the universities can prove under strict scrutiny that its practices further a “compelling interest” and that they are “narrowly tailored” for that interest.

The precedent around what was considered constitutional and what was not was reexamined in Gratz v. Bollinger and Grutter v. Bollinger. In Gratz, two white students applying to one of the University of Michigan’s undergraduate programs were rejected, and claiming that it was because of their race, they filed a suit against the school. Investigation of the Office of Undergraduate Admissions (OUA) for the University of Michigan found that the OUA did their admissions based on a point system, where being an underrepresented minority would earn the applicant twenty extra points. In this decision, the Supreme Court upheld that the policy gave an unfair advantage based on race, one where race could be the deciding factor in admissions. This policy was deemed unconstitutional under the 14th Amendment, as it was not narrowly tailored enough to survive strict scrutiny.

Grutter v. Bollinger, however, turned out differently. In Grutter, a white student applying for Michigan Law was rejected despite having a relatively high GPA and high test scores. He sued the school for discriminatory practices, as it admitted to using race as one factor out of many in its admissions process because the school had a “compelling interest in achieving diversity in its student body.” In Grutter, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of affirmative action, stating that because the school practiced holistic review, where applicants were looked at in a highly individualized way, race could not be the deciding factor in admissions, and therefore, the school passed the threshold of strict scrutiny and the policy was deemed Constitutional, upholding the idea of race-conscious admissions.

In 2015, SCOTUS once again upheld affirmative action in Fisher v. University of Texas. The Court upheld that the university’s process of holistic review, which included race as a factor out of many, was narrowly tailored to serve a compelling state interest that was laid out in a detailed, concrete goal.

These previous cases then lead back to the present, with the decisions on Harvard and UNC, effectively ending affirmative action and overturning Grutter, according to Justice Clarence Thomas.

The Future of Affirmative Action

In 2022, conservative advocacy organization, Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA), brought two cases in front of the Supreme Court and left with the victory that opponents to affirmative action had been looking for for years. In suing Harvard and the University of North Carolina, SFFA effectively overturned Grutter v. Bollinger. In the decision, the Supreme Court changed precedent: encouraging diversity for the benefits it could have on the education of the student body was no longer a compelling interest to justify the use of race based affirmative action.

In essence, strict scrutiny got much stricter. This decision sets a precedent that effectively renders most forms of race-conscious admissions impermissible under the Constitution. With little forms of affirmative action left to be practiced, it begs the question: what now?

The decision does not ban students from talking about race and its impacts on them in their applications. As Justice Roberts said in the decision, “the student must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual—not on the basis of race.” Students should not be discouraged from talking about their race and its impact on them, but unlike before, they are also not guaranteed that the impacts of their race, negative or positive, may be taken into consideration during the application process.

These considerations, though, were critical for encouraging diversity on campus. In the nine states that had banned race-conscious admissions programs in higher education through state legislation before the case was decided, schools were already noticing a drop in diversity, even though some invested in diversity pipeline initiatives within their communities. Only time will tell if the rest of the nation will follow suit.

The goal of affirmative action and race-conscious admissions has always been to close the gap between white people and people of color that has been created through centuries of colonialism, slavery, segregation, and discrimination, and it is clear that the legacies of those injustices are not gone. Black and brown students are underrepresented in gifted programs, they are disciplined at disproportionately higher rates at school than their white counterparts, and they score much lower on standardized tests like the SAT than their white and Asian peers. These disparities are not only a reflection of the years of disenfranchisement of black and Hispanic Americans, but they continue to be the factors that lead to their lower levels of enrollment in college, which ultimately leads to a never ending cycle of disenfranchisement. Affirmative action was the tool universities across the nation used to attempt to fix these problems. However, with the recent ruling and the gutting of affirmative action as we know it today, schools will have to find other ways to promote diversity and equity within their institutions.

Some schools have tried to promote diversity on their campuses by no longer requiring students to send in their standardized test scores and changing how they look at applicants and measure merit. Despite this, there are still gaps left in diversity and equity across college campuses. With or without affirmative action, there will still be inequalities in the education system. It will take deliberate action by colleges and universities, as well as state and federal governments, in order to dismantle the systems of inequality in the absence of affirmative action.

Want to get involved?

Connect with us! Connect with us!